“Foundations of Western Liberty”

Hier ein weiterer Auszug aus einer zweiten längeren Arbeit für das Lithuanian Free Market Institute (Lietuvos laisvos rinkos institutas), einer privaten Wirtschaftsforschungseinrichtung in Vilnius, zum Thema, „scarcity“ – Mangel oder Knappheit.

The only divine-human Mediator

Freedom is needed everywhere, but it is most important is to keep the power of the state within bounds to preserve this freedom. This is only achievable if the civil government is not divine and not called to save us.

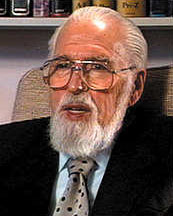

The Calvinist philosopher and theologian Rousas J. Rushdoony (1916–2001) elaborated on this in The Foundations of Social Order (1998). In the chapter “Foundations of Western Liberty” he explains the political implications of the Chalcedon Formula (or definition), which was accepted and proclaimed at the Fourth Ecumenical Council of the Church in Chalcedon in 451. The Formula “made possible the development of liberty” because it “handed statism its major defeat in man‘s history”, Rushdoony writes. He regards true liberty “as a product of Christian faith, because antiquity saw the city state or the imperial state as a religious entity.”

The message of Chalcedon was that Christ is the only divine-human Mediator. The Formula summarised the orthodox doctrine of the two natures in Christ: He is “at once complete in Godhead and complete in manhood, truly God and truly man”, “of one substance with the Father as regards his Godhead, and at the same time of one substance with us as regards his manhood”. The distinction of natures is safeguarded, “the characteristics of each nature” are preserved, but not in such a way that the natures are separated. There are not two personalities in Christ, a divine and a human; the two natures “form one person”; there is “but one and the same Son… the Word, Lord Jesus Christ”. In the centre of the Formula are the four famous negations concerning the relations of the two natures: “without confusion, without change, without division, without separation”.

At first glance it seems that these words of pure theology are not relevant for our political context. But Rushdoony explains that the Formula …

“separated Christian faith sharply from the Greek and pagan concepts of nature and being. It made it clear that Christianity and all other religions and philosophies could not be brought together. The natural does not ascend to the divine or to the supernatural. The gulf is bridged only be revelation and by the incarnation of Jesus Christ. Salvation therefore is not of man nor by means of man‘s politics, or by any other effort of man.”

In antiquity the state as the highest power on earth manifested the incarnate divinity in the political realm. The ancient state governed the souls. Chalcedon taught that only in Christ do divinity and humanity join together. Therefore human institutions are not incarnations of the deity able to unite the unseen and seen worlds. As a result, “The state was reduced to a human order, under God, and it was denied its age-old claim to divinity for the body politics, the ruler, or the officers.”

The state is not a divine-human order. This negation can be traced back to the Old Testament: in Israel priest and king were separate offices; the king was first of all the civil ruler, the high priest his religious counterpart. The prophets, often criticizing the rulers, and priests were standing next to the kings. Here we have already the seed of our modern separation of state and church.

“Western liberty began when the claim of the state to be man‘s savior was denied.” The state is not god because there is another God to whom everyone is responsible: “In antiquity man had been bound to the state but ‘freed’ from God. Orthodox Christianity freed man from the state by binding him to God, who is man‘s true ground of freedom and fulfilment. The source of Christian liberty is trinitarianism, with its logical concomitant, Chalcedonian Christology.”

Jan Assmann makes the same point in Die Mosaische Unterscheidung: The Egyptian king was mediator of salvation and at the same time embodiment of divine attention to humanity. Monotheism, in contrast, made salvation the work of God alone and thus removed it from the influence of institutions of the state. What remains in Israel is a sovereign who has to deeply bow to the Torah, the Mosaic Law, and study it day and night.

Inventing the Individual

It is interesting to see that Oliver O‘Donovan from Oxford makes similar claims in The desire of nations (1996). The message of Christianity “is a paradigm for the birth of free society, grounded in the recognition of a superior authority which renders all authority beneath it relative and provisional.” Christ, the awaited King has come, and thus “God has done something which makes it impossible for us any more to treat the authority of human society as final and opaque… he has loosened the claims of existing authority, humbling them under the control of his own law of love”. He also regards freedom first of all as “a social reality, a new disposition of society around its supreme Lord which sets it loose from its traditional lords”. We have “freedom to freely obey Christ.”

In the late 19th century Abraham Kuyper was (next to Lord Acton) one of the most outstanding advocates of freedom. The theologian, politician and journalist famously outlined a biblical, neo-Calvinistic worldview in his Lectures on Calvinism (1898). Kuyper underlines that God enters into fellowship with every person, therefore “every man and every people [is placed] before the face of our Father in heaven.” Because there is just one ultimate King “the knee is bowed to God, while over against man the head is proudly lifted up.” Human beings are under God, but that also implies that “as man I stand free and bold, over against the most powerful of my fellow-men.” God alone is the ultimate Sovereign and thus “all authority of governments on earth originates from the Sovereignty of God alone. When God says to me, ‘obey,’ then I humbly bow my head, without compromising in the least my personal dignity, as a man.” The ultimate sovereignty of God leaves space for “sovereignty in the individual social spheres” where the state must not intrude.

But why do so many scholars see the roots of freedom in pagan antiquity and not in Israel or Christianity? Ludwig von Mises claims in The Anti-Capitalistic Mentality (1956) “that the idea of liberty originated in the cities of ancient Greece.” He mentions “the rule of law”, independent courts etc. We won‘t argue the case here that the primacy of law and not the will of the king is an ‘invention’ of Israel. Let us concentrate on the issue of human rights and freedom.

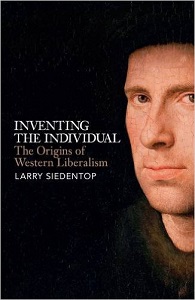

Larry Siedentop in Inventing the Individual (2014) excoriates the myth of a free and secular ancient Greece and Rome. In the chapter on the ancient family he turns our attention to the fact that the Roman paterfamilias, the head of the family, acted as high priest in his family. There were no individual rights and no personal freedom as we understand it today. The often anti-clerical thinkers of the Enlightenment …

Larry Siedentop in Inventing the Individual (2014) excoriates the myth of a free and secular ancient Greece and Rome. In the chapter on the ancient family he turns our attention to the fact that the Roman paterfamilias, the head of the family, acted as high priest in his family. There were no individual rights and no personal freedom as we understand it today. The often anti-clerical thinkers of the Enlightenment …

“failed to notice that the ancient family began as a veritable church. It was a church that constrained its members to an extent that can scarcely be exaggerated. The father, representing all his ancestors, was himself a god in preparation… The authority of the father as priest and magistrate initially extended even to the right to repudiate or kill his wife as well his children.”

Society, Siedentop underlines, was not understood “as an association of individuals”. “Charity, concern for humans as such, was not deemed a virtue, and would probably have been unintelligible.” Our notion of a human dignity possessed by every person was virtually unknown. The dignity of human beings depends on the doctrine that all are made in image of God. Certainly the freedom in cities of ancient Greece was greater than in empires of the East; but only a small minority of inhabitants benefited from this freedom.

New godplayers

In modern secular societies belief in God to whom everyone is responsible is on the decline. This cultural development makes room again for statism, the belief that the state has a god-like function. Modern states tend to be omnipresent and omnipotent; people hopefully expect the solution to almost every problem from the state. The divinized state easily fills the void created by modern secularism. Now people believe less in an eternal and blessed afterlife, now the life here and now has to become as blissful as possible.

For centuries the state‘s hands were tied through quite strict budget control. The existence of central banks and the ‘inventing’ of fiat money made it possible to create out of nothing – ex nihilo, formerly the prerogative of God. With the help of central banks politicians and public servants in the state became godplayers (see Roland Baader‘s Geld, Gold und Gottspieler). This is so seductive because even now it seems possible to overcome scarcity altogether. If the state has in its hands a horn of plenty, why not delight citizens (and voters) with a never-ending stream of abundant blessings? Freedom is in danger of being sacrificed.

God is man‘s true ground of freedom. This conviction has to be regained if we want to push back statism, the divinization of the state.